Kenneth Traywick and Alabama’s Assumption of Divine Authority

Chekhov warned against states that assume divine authority. Alabama ignored him.

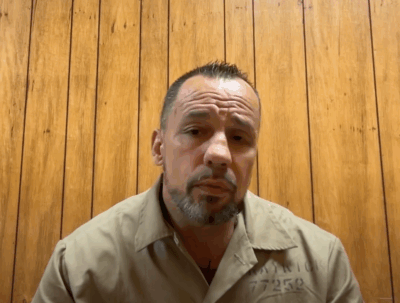

What is unfolding around Kenneth Traywick is not a sudden emergency. It is the result of warnings delivered in advance, acknowledged in silence, and followed by opaque action without explanation. By Day 35 of his hunger strike, Swift Justice formally notified the Alabama Department of Corrections, its medical contractor YesCare, and food services provider Aramark that the situation had reached a point of acute medical risk. Five weeks without food is not ambiguous terrain. It is a threshold beyond which deterioration is predictable, complications are well documented, and the need for transparent medical oversight is not optional but essential.

Those warnings did not ask for indulgence or exception. They asked for communication: written clarification of medical protocols, meaningful family contact, and safeguards proportionate to the risk created by prolonged starvation. They asked, in effect, that the State acknowledge the gravity of a situation it had already allowed to develop.

By Day 36, a significant medical intervention occurred. The family was given no advance notice. No written explanation followed. There was no disclosure of the clinical rationale, the supervising authority, or the care framework governing what had been done to a man whose body had been deprived of nutrition for more than a month. At the same time, conflicting information circulated about whether Traywick had resumed any form of intake at all—information never clarified by ADOC or YesCare, despite the well-known dangers of refeeding after extended starvation.

By Day 37, the record was unmistakable: repeated requests for clarity had been met with administrative silence. No written intake protocols. No description of monitoring. No escalation plan. This was not a failure of foresight. It was a failure of responsibility.

What compounds the medical risk is the deliberate isolation of the family. Communication has been restricted to the point where those closest to Traywick have been left without confirmation of basic facts—what care he is receiving, what monitoring is in place, or who is accountable for decisions being made in his name. In a system already shielded from public scrutiny, the exclusion of family members removes one of the last remaining forms of informal oversight.

The following message, shared privately by Traywick’s wife with supporters, illustrates that isolation without resorting to exaggeration or rhetoric. It is presented here in full because its restraint is precisely what makes it so difficult to dismiss:

“I want to share a brief update as carefully and honestly as I can.

Early yesterday, another inmate contacted me to let me know that Swift has paused the hunger strike temporarily to preserve his health and that he is receiving some form of liquid diet. At this time, this information has not been confirmed or explained by ADOC or YesCare, as they continue to refuse to communicate details about his care with me or anyone else.

Because ADOC and YesCare will not provide clear information, it has been very difficult to give consistent updates to Swift’s close friends and family.

What continues to deeply concern me is that we still have no confirmation that Swift is being properly monitored for heart issues, blood pressure and blood sugar, liver and kidney function, or muscle deterioration after more than five weeks without food. These are pre-existing conditions for Swift, and recovery after prolonged starvation carries serious risks if not carefully managed.

If you are able, please continue calling and applying pressure to ADOC and YesCare to ensure that Swift receives appropriate medical monitoring, transparency, and humane care.”

To understand why a hunger strike reaches this point—and how it is normally handled inside Alabama’s prisons—it is necessary to listen to those who live within the system. Bernard Jemison, currently incarcerated at a different Alabama facility, responded to a series of questions about conditions, grievance procedures, and hunger strikes based on his own experience as an inmate activist.

Jemison describes chronic food deprivation as a baseline condition, noting that his facility routinely fails to meet even ADOC’s own menu standards. Meals frequently lack adequate calories, with breakfasts consisting of little more than bread and hot dogs—portions he describes as markedly inferior to those served at other facilities. This deprivation, he emphasizes, is not incidental. It is normalized.

When asked about grievance procedures, Jemison explains that the system is functionally limited, applying primarily to medical complaints and offering little recourse for broader conditions of confinement. Even then, success is sporadic. Only recently, after persistent effort, was his own complaint regarding access to outdoor recreation addressed. The implication is clear: formal mechanisms exist largely on paper.

Regarding hunger strikes, Jemison speaks from direct participation. He describes them as a recognized, if extreme, method of protest inside Alabama prisons—one that typically produces results precisely because of the liability it creates for administrators. In his experience, extended hunger strikes are taken seriously; wardens often grant reasonable requests rather than risk escalation.

Against that backdrop, what he has heard about Swift Justice’s case is alarming. Jemison reports that standard procedures—daily weight checks, vital signs, blood and urine monitoring—have not been followed. If accurate, this represents not neglect at the margins, but deviation from established practice in a situation where the risks are most acute.

Asked what Swift Justice is ultimately seeking, Jemison’s answer is blunt in its simplicity: fair and humane treatment. Nothing extraordinary. Nothing indulgent. Simply recognition of basic human worth within a system that, as he puts it, assigns little value to the lives of the incarcerated. Referencing The Alabama Solution, Jemison situates Swift’s hunger strike within a broader culture in which suffering is not merely tolerated but rationalized as deserved.

What is happening to Kenneth Traywick is not an aberration, and it is not a bureaucratic mishap. It is the predictable outcome of a system that treats incarcerated people as expendable and then insulates itself from scrutiny when that expendability becomes dangerous. Alabama has constructed a prison regime in which deprivation is routine, grievance mechanisms are largely performative, and extreme acts of self-harm become one of the few remaining ways to force acknowledgment. When those acts succeed in drawing attention, the response is not transparency but secrecy.

At this stage, ignorance is no longer plausible. ADOC, YesCare, and the State of Alabama have been placed on notice repeatedly. They have been warned about the medical risks. They have been asked—explicitly and in writing—for clarity, oversight, and communication. They have chosen opacity instead. That choice carries consequences. When a government exercises total control over a person’s body while withholding information from family, advocates, and the public, it is no longer administering custody; it is asserting dominion.

Anton Chekhov warned against the conceit of institutions that assume the authority to decide who may suffer and to what extent. Alabama has ignored that warning. It has positioned itself as final arbiter over life, health, and silence, while denying even the minimal transparency that would allow its actions to be judged. This is not governance. It is moral abandonment dressed up as procedure.

If Kenneth Traywick is harmed, it will not be because the risks were unknowable. It will be because those empowered to intervene chose not to be accountable. And if the State of Alabama is permitted to continue exercising this level of unchecked power behind prison walls, then responsibility does not rest solely with corrections officials or contractors—it extends to a public that has been taught to accept suffering as policy and silence as normal.

That is the indictment.

by: Guest Contributor, Will Hazlitt and the Editorial Board of The Intelligencer